The Season of Laughter

It was the spring of laughter. Or maybe the fall. Seasons lost their edges here long ago. In Ardona, the scent of air changes by decree—cinnamon for winter, lilac for summer, lemon for gratitude season. No one knows the sky anymore. They watch Feeling Forecasts instead.

Frivolity is law here—not written, but lived. Ardona does not ban sorrow. It simply outshines it. Mourning is allowed, but only in designated Quiet Zones with background music and digital hugs.

I used to teach at The Lyceum of Free Inquiry, before they shuttered it during the Rebalancing. The last true institution of open thought. We had no slogans, only questions. That made us dangerous.

My last lecture was on Camus. “Sisyphus is the absurd hero,” I said to a vacant hall. “Because he continues.” Then I bowed to the wall, gathered my bag, and walked into irrelevance.

They gave me a termination ribbon: lemon-scented, stitched with a smiling sun. A mercy, they said. We were being “de-platformed gently.”

My wife left just before that.

We had fought about it—once.

It was during the first spring of the Rebalancing, when the Lyceum was still holding silent debates in the courtyard under the fig trees. The regime hadn’t declared war on thought yet—only hinted at it, like a cough in a quiet room.

That evening, I had just returned from a symposium on moral agency in artificial environments. She was seated at the kitchen table, holding a thick envelope—our son’s acceptance to the National Academy for Civic Renewal.

“He’s brilliant,” she said. “He’ll be safe there. He’ll be useful.”

I stood at the doorway, still wearing my academic robe. “Useful to whom?” I asked.

“To himself,” she said, but her voice cracked on the word.

I remember the smell of olives on the table. I remember her thumb, stained with ink from sealing the application.

That was the last fight we had that wasn’t silent.

We had stopped speaking about ideas. About anything. She watched the first “Harmony Tribunal” like others watched theater. A woman’s trial was live-streamed. The verdict was voted on through emojis. The woman smiled as she was sentenced—for setting “a disruptive emotional tone” during a school recital.

Later that night, my wife said, “Maybe it’s not justice, but it is order.” The next morning she left. I didn’t stop her.

I’ve since wondered: Did she leave because I refused to adapt? Or because she was afraid of being near someone who didn’t?

But it was my son who broke me.

Once my student. My disciple. Now the Director of the House of Vibrance—the regime’s cultural ministry.

When he got the appointment, he didn’t tell me. I found out through a broadcast where he unveiled the new state slogan: “Authenticity is Alignment.”

He smiles like an actor now. Speaks in rhetorical flourishes that mean nothing but sound good enough to chant. He erased the archives of the Lyceum. I watched him do it live. He looked proud.

He stood at the center of that stage like a preacher at the end of history.

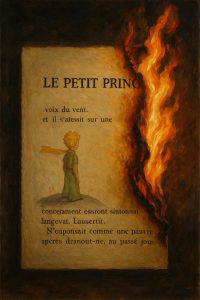

And for a moment, I saw him as a boy again—seven years old, barefoot in the reading alcove of our old flat, clutching a copy of Le Petit Prince. He used to ask, “Is this book true?” and I’d answer, “It’s truer than most facts.”

He believed me, then.

He would fall asleep with books on his chest, whispering phrases he didn’t understand yet but trusted. I used to think that was the measure of faith—a child believing a sentence will mean more tomorrow.

And now here he was, burning tomorrow’s meaning.

I don’t know when he stopped asking questions. Perhaps it was when he joined the National Academy, where joy replaced inquiry and certainty wore a badge. Maybe the questions were still there, buried under his smile, screaming through the broadcast delay.

Or maybe not.

Maybe belief, like memory, is not lost in a single act—but in a thousand affirmations of something you never believed to begin with.

The ceremony was held in the Center of Public Clarity. Thousands cheered. Behind him, holograms of burning books danced like ghosts. He declared it an act of “emotional hygiene,” the cleansing of what he called “linguistic debris from the age of overthinking.”

I knew the words he used. They were once mine. He had studied my lectures on clarity, precision, moral rhetoric. He’d weaponized them into slogans.

It is a strange thing—to hear your own thoughts twisted into propaganda. Like watching your reflection mouth lies behind glass. He called them “dangerously inert.”

I sent him a message.

“Do you remember Neruda? Do you remember your mother’s laugh?”

It was marked Seen, but not replied to.

I walk daily. It’s still legal. District Marid once teemed with thinkers and provocateurs. Now it’s a wellness mall of mirrors and echo pods. Every five meters, a screen reminds us:

Your Mood Is Your Responsibility.

They’ve renamed the Lyceum. It’s now The Ardona Institute of Emotional Excellence. They teach Vibrance, Optimism Rhetoric, and Civic Expression Dance. The students are always smiling. Most have never read a full book. They say summaries preserve clarity.

And then there’s the Museum of the Forgotten.

Inside, a wax figure of me stands beneath a plaque:

“The Sad Man of Thought.”

Tourists pose beside it. Children press buttons to make me say things like “Truth matters” or “Read more books.” Then they laugh. I’ve become a nostalgic caricature—a scarecrow of too much thinking.

Last month, I saw a group huddled in the square. Close. Unsanctioned.

One held a book.

A real book.

Lior.

She was expelled from the Lyceum for writing that the national anthem used rhythmic compliance techniques. I remember defending her. It did not help.

“We’re gathering,” she whispered. “Under the tramline. Midnight.”

I went home and sat in silence. Thought of my wife. Her mouth trembling with doubt that last week. “If we’re not smiling,” she said, “aren’t we just inviting the fall?”

Beneath the tramline, it smelled of rust and rot. Candles flickered. Books lay like relics between them. They passed me Dalis’s notebook. He’d disappeared after arguing against Emotional Uniformity in his thesis.

“Pleasure is pacification,” he’d written.

“Memory is the last rebellion.”

They called themselves The Unechoed.

“We remember,” Lior said.

I spoke of Camus again. “In an unfree world, to be absolutely free is to exist as defiance.”

They didn’t cheer. They listened. One boy asked if resistance meant violence.

“No,” I said. “Violence is loud obedience in disguise.”

Then a girl asked if remembering was enough.

I hesitated.

“It has to be,” I said. “Because remembering is the only truth that can’t be forced.”

They didn’t seem satisfied.

Good. They shouldn’t be. That meant more.

Renzo was waiting in my apartment.

“You were seen.”

“I know.”

“They won’t arrest you. You’re archived. But the kids—they’re different. They don’t know the rules of controlled resistance.”

I looked at him. “What do you believe?”

He hesitated. “I believe in silence. It’s the only thing they haven’t co-opted.”

I disagreed. They’ve silenced silence, too. They fill it with curated stillness—Meditation Hours, Mindful Slogans, Cleansing Colors.

“Careful,” he said. “Your son signed off on Quieting Orders last week. Memory therapy is trending again.”

Weeks passed.

The Unechoed grew.

We read Arendt, Huxley, Audre Lorde, Orwell. We whispered. We remembered.

One night, a teenage girl read The Plague. Her JoyWatch blinked crimson. After the final line, she took it off and smashed it under her boot.

Lior touched my shoulder.

“You gave us language,” she said.

“No,” I replied. “I reminded you of silence.”

I dreamed of my wife again. We were in our old kitchen. She was barefoot, whispering Neruda. “I want to do with you what spring does with the cherry trees.” The lines were trembling in her voice. She never recited them after our son was promoted.

I awoke with wet eyes and ink-stained hands.

I had begun writing again.

Not memoir.

A story.

Then the new boy arrived. Pale, sharp-eyed. He carried a badge.

A Harmony Cadet.

Lior rose, tense.

“I’m not here to report,” he said. “I’m here to understand.”

He held out a worn textbook: Rhetoric and Civil Thought. My name was inside.

“You taught my father. He was taken for refusing joy. He told me that truth sounded different when you spoke.”

That night, the boy read aloud. And no one interrupted.

It is winter again.

The State Hour of Cheer plays on repeat. My son’s face fills every screen. He now hosts Policy Parade, where citizens vote on slogans. The top three are made law. Last week’s winner was:

“Harmony Is Heritage.”

I watched as he laughed too hard. The kind of laughter that sounds like drowning.

There’s a rumor—started softly, in our circles—that the Emissary himself failed a Mood Audit. That his smile is synthetic now. That the House of Vibrance is vetting replacements more “emotionally compelling.”

Even tyrants grow tired of pretending.

There are signs.

The official colors have changed four times this year—blue, then saffron, then coral, then teal. No one seems to know why. The Prime Emissary wears different expressions each week, none of them real. His laughter sounds like it’s been dubbed over.

People say “We’re aligned” the way people used to say “We’re fine” during wartime. Too quickly. Too brightly.

Even Renzo, who once called silence a fortress, confessed last week: “I haven’t felt joy in two years. But I’ve performed it a thousand times.”

The collapse may not come with screams. It may come with applause thinning into static.

Last night, I gave Lior a manuscript.

Earlier that day, I almost burned it.

I held the pages in my hand, trembled with the thought that even stories might betray you. That memory could become poison in the wrong mouth. That if we failed—truly failed—it would be better to leave no record behind at all.

But then I thought of the girl with the JoyWatch. Of her shaking voice as she read The Plague. Of Renzo’s whispered confessions. Of my wife’s thumb, stained with ink.

I smoothed the page.

Wrote one more sentence.

Lit a candle.

And waited for night.

She read the title—“The Season of Laughter”—and asked, “Is it about us?”

“No,” I said. “It’s about what comes next.”

She didn’t reply.

She just lit a candle.

The flame flickered.

We passed the story hand to hand like contraband. No one read aloud. They just held it, eyes scanning as if touching truth might burn them.

When the boy who’d brought his father’s textbook handed it back to me, he whispered, “Will this survive?”

I looked at the words I’d carved from exile, memory, grief.

“If we’re lucky,” I said, “it won’t. Because what it says will already be known.”

They will come soon. Not for me. For someone.

That is how tyrannies of joy survive. They do not burn books. They bleach them. They do not erase minds. They entertain them into forgetting.

But beneath the rails, in flickering candlelight, we remember.

And in Ardona, where forgetting is law,

remembering is war.

Tonight, we meet in a deeper tunnel. The tramline above has grown too loud—an automated announcement now plays every hour: “Your joy ensures your neighbor’s freedom.”

We read in shifts now.

Some bring food. Others bring silence. And one girl, a painter, has begun sketching our faces—not as we are, but as we were before the forgetting.

When the girl finished sketching, she handed me the page.

It was my face—but not mine. Younger. Clear-eyed. A quiet intensity lit the contours. Behind me, she’d drawn not the Museum, not the Lyceum, but a page on fire.

Her drawing of me shows no sorrow.

Only fire in the eyes.

I am no longer the Sad Man of Thought.

I am the father of no son.

I am the husband of a memory.

I am the keeper of the ember.

And the ember is catching.

The End